Time series forecasting has undergone a transformation with the emergence of foundation models, moving beyond traditional statistical methods that extrapolate from single time series. Building on the success of the original Chronos models — which have been downloaded over 600 million times from Hugging Face — Amazon researchers introduce Chronos-2, designed to handle arbitrary forecasting tasks in a zero-shot manner through in-context learning (ICL).

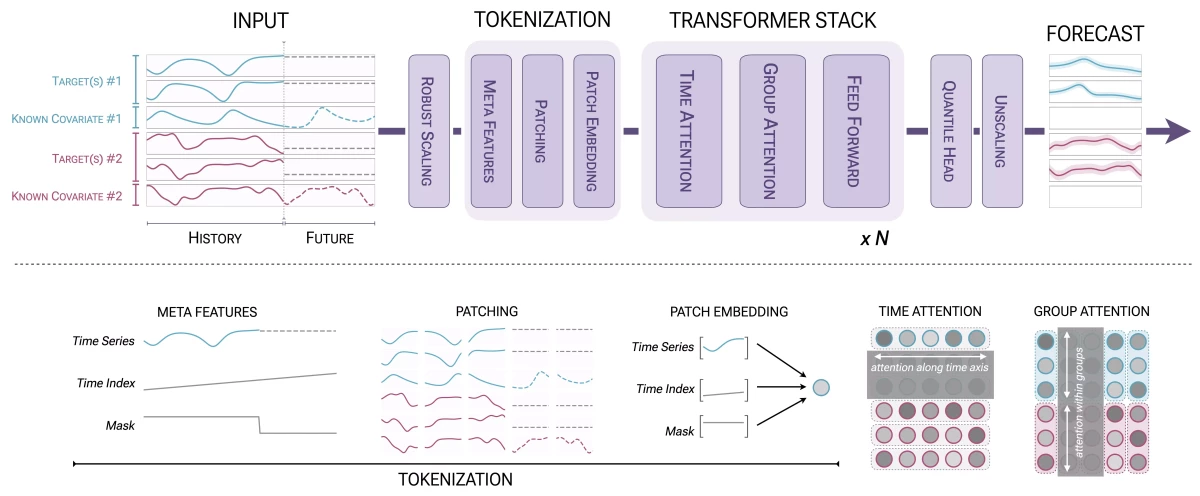

The complete Chronos-2 pipeline. Input time series (targets and covariates) are first normalized using a robust scaling scheme, after which a time index and mask meta features are added. The resulting sequences are split into non-overlapping patches and mapped to high-dimensional embeddings via a residual network. The core transformer stack operates on these patch embeddings and produces multi-patch quantile outputs corresponding to the future patches masked out in the input. Each transformer block alternates between time and group attention layers: the time attention layer aggregates information across patches within a single time series, while the group attention layer aggregates information across all series within a group at each patch index. The figure illustrates two multivariate time series with one known covariate each, with corresponding groups highlighted in blue and red. This example is for illustration purposes only; Chronos-2 supports arbitrary numbers of targets and optional covariates. Unlike its predecessors, which supported only univariate forecasting, Chronos-2 can jointly predict multiple coevolving time series (multivariate forecasting) and incorporate external factors like promotional schedules or weather conditions (covariate-informed forecasting). For example, cloud operations teams can forecast CPU usage, memory consumption, and storage I/O together, while retailers can factor in planned promotions when predicting demand. The model's group attention mechanism enables it to capture complex interactions between variables, making it particularly valuable for cold-start scenarios where limited historical data is available.

Quantum computing has long promised exponentially faster computation for certain problems, but quantum devices’ extreme sensitivity to environmental noise has limited practical applications. Amazon Web Services' new Ocelot chip represents a breakthrough in addressing this challenge. Ocelot uses bosonic quantum error correction based on "cat qubits", named after Schrödinger's famous thought experiment.

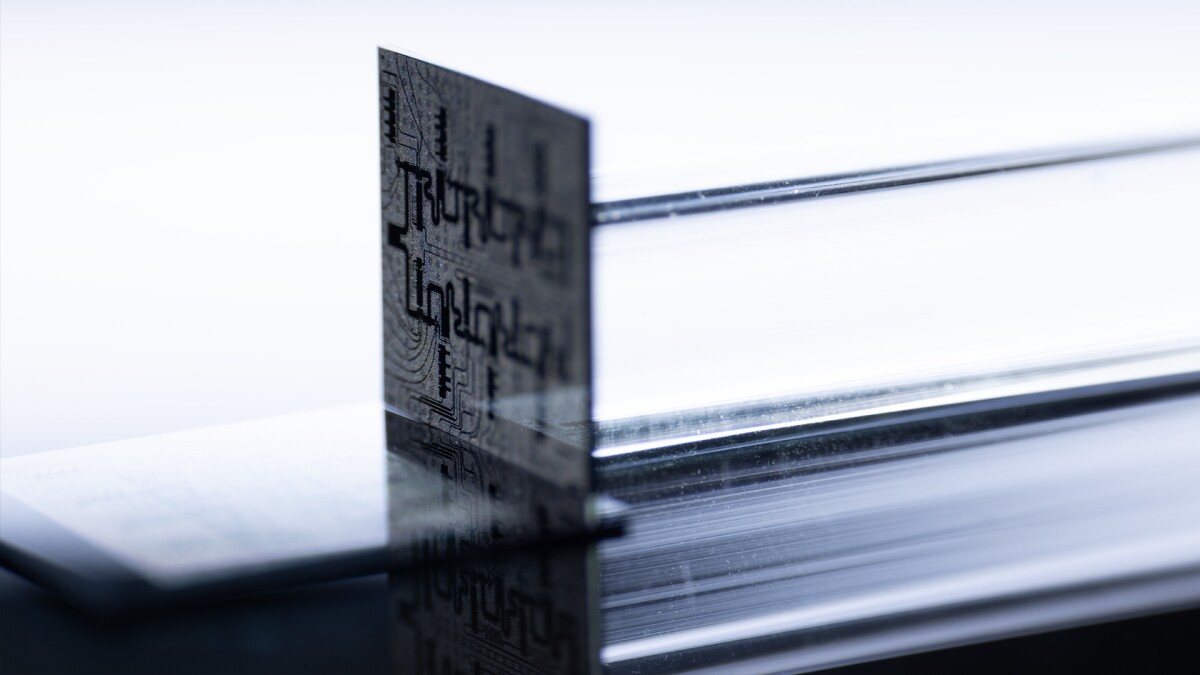

The pair of silicon microchips that compose the Ocelot logical-qubit memory chip. Traditional quantum error correction methods require thousands of physical qubits per logical qubit to achieve usable error rates, creating an enormous resource overhead. Ocelot's innovative architecture exponentially suppresses bit-flip errors at the physical level while using a simple repetition code to correct phase-flip errors. This approach achieves bit-flip times approaching one second — more than a thousand times longer than conventional superconducting qubits — while maintaining phase-flip times sufficient for error correction. The result is a distance-5 error-correcting code requiring only nine qubits total, versus 49 qubits for equivalent surface code implementations.

As agentic AI systems move from concept to reality, fundamental scientific questions emerge about how these systems should share information and interact strategically. Amazon Scholar Michael Kearns explores several research frontiers that will shape the development of AI agents capable of acting autonomously on users' behalf.

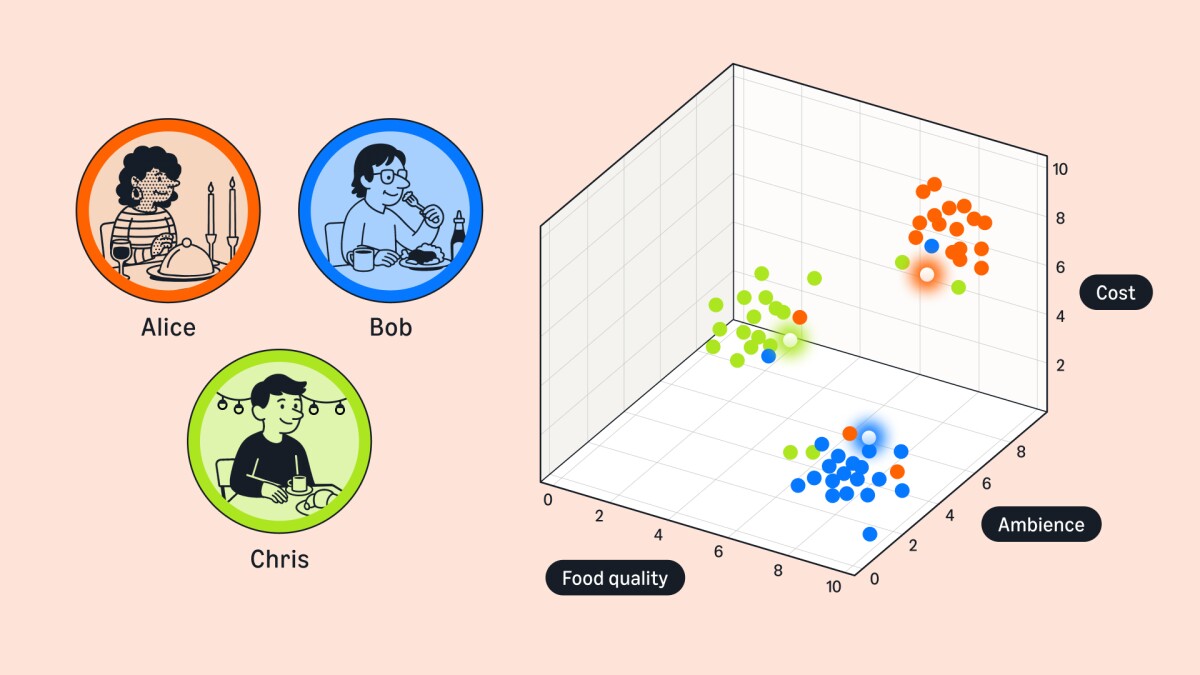

One intriguing question is what language agents will speak to each other. While agents must communicate with humans in natural language, agent-to-agent communication might be more efficient in the native "language" of neural networks: embeddings, where meanings are represented as vectors in a representational space. Just as websites today offer content in multiple human languages, we may see an "agentic Web" where content is pretranslated into standardized embeddings.

In this example, the red, green, and blue points are three-dimensional embeddings of restaurants at which three people (Alice, Bob, and Chris) have eaten. (A real-world embedding, by contrast, might have hundreds of dimensions.) Each glowing point represents the center of one of the clusters, and its values summarize the restaurant preferences of the corresponding person. AI agents could use such vector representations, rather than text, to share information with each other. Context sharing presents another challenge: agents must balance the benefits of sharing working memory with privacy concerns. When your travel agent negotiates with a hotel booking service, how much context about your preferences should it share — and how much financial information should it withhold?

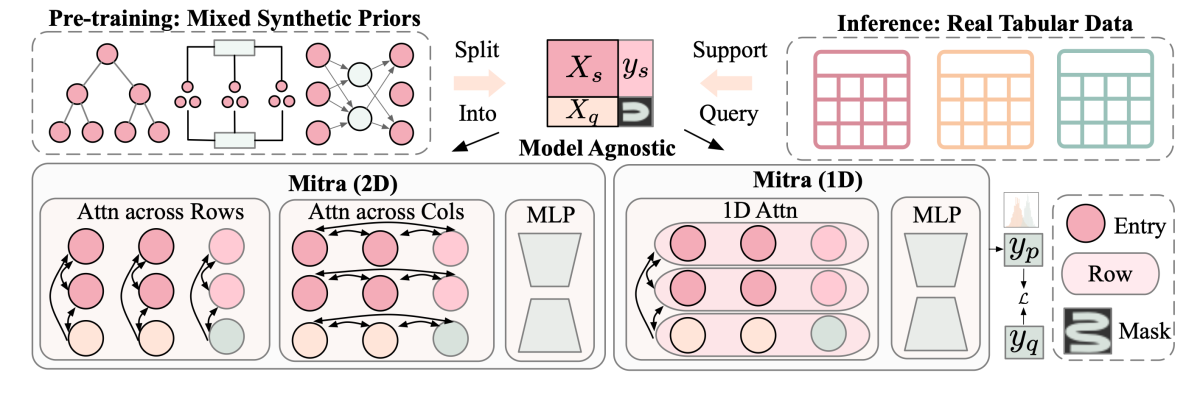

Inspired by how large language models are trained on diverse text corpora, Amazon researchers developed Mitra, a tabular foundation model pretrained entirely on synthetic datasets. While this may seem counterintuitive, real-world tabular data is often limited and heterogeneous, making it more practical to simulate diverse patterns that cover a wide range of possible data distributions.

The key insight behind Mitra is that the quality of synthetic priors determines how well the model generalizes. Effective priors yield good performance on real tasks, exhibit diversity to prevent overfitting, and offer unique patterns not found elsewhere. Mitra's training mixture includes structural causal models — which combine graphs of causal dependencies with probabilistic equations — and popular tree-based methods like gradient boosting, random forests, and decision trees.

Overview of the Mitra framework. We pretrain tabular foundation models (TFMs) on a mixture of synthetic data priors, including structural causal models and tree-based models. Each dataset is split into support and query sets. Mitra supports both 2-D attention across rows and columns and 1-D row-wise attention. At inference, the model conditions on support examples from real datasets to predict query labels using in-context learning (ICL) without gradient updates. Released as part of AutoGluon 1.4, Mitra demonstrates state-of-the-art performance through in-context learning: it can predict labels for new datasets when conditioned on a moderate number of examples, without requiring gradient updates or task-specific training.

When Amazon Aurora launched in 2015, it promised to combine the cost effectiveness of MySQL with the performance of high-end commercial databases. The key innovation was decoupling computation from storage, a departure from traditional database architectures.

By moving durability concerns to a separate, purpose-built storage service and offloading caching and logging layers to a scale-out, self-healing system, Aurora addressed the central constraint in cloud computing: the network. This service-oriented architecture protects databases from performance variance and failures while enabling independent scaling of performance, availability, and durability.

In their 2017 paper, Amazon researchers describe the architecture of Amazon Aurora. Over the past decade, Aurora has continued to evolve. Aurora Serverless, introduced in 2018, brought on-demand autoscaling that lets customers adjust computational capacity based on workload needs, using sophisticated resource management techniques including oversubscription, reactive control, and distributed decision making. As of May 2025, all Aurora offerings are now serverless: customers no longer need to choose specific server types or worry about underlying hardware, patching, or backups.

Converting unstructured or poorly structured data into clean, schema-compliant records is a critical task across domains from healthcare to e-commerce. While large language models can perform this task when prompted with schema specifications, this approach has drawbacks: high costs at scale, complex prompts, and limitations on the complexity of the schemas.

In a pair of recent papers, Amazon researchers introduced SoLM (the structured-object language model), a lightweight specialized model trained to generate objects in specific schemas using a novel self-supervised denoising method. Rather than training SoLM on clean examples, the researchers take existing structured records, introduce artificial noise, and train the model to recover the original forms. By making the noise increasingly aggressive — even completely removing structure or randomly shuffling tokens — the researchers enhance the model’s quality and teach it to operate on completely unstructured input.

A key innovation is confidence-aware substructure beam search (CABS), which applies beam search at the level of key-value pairs rather than individual tokens, using a separately trained confidence model to predict each pair's probability. This approach dramatically improves accuracy while mitigating hallucination risks.

Traditional embedding-based information retrieval compares a query vector to every possible response vector in a database, a time-consuming process as datasets grow. Amazon's GENIUS (generative universal multimodal search) model takes a different approach: instead of comparing vectors, it uses input queries to directly generate ID codes for data items.

With embedding-based retrieval (a), a text embedding must be compared to every possible image embedding, or vice versa. With generative retrieval (b and c), by contrast, a retrieval model generates a single ID for each query. With GENIUS (c), the first digit of the ID code indicates the modality of the output. Presented at CVPR 2025, GENIUS is a multimodal model whose inputs and outputs can be any combination of images, texts, or image-text pairs. Two key innovations enable GENIUS's performance. The first is semantic quantization, where IDs are generated piecemeal, with each new ID segment focusing in more precisely on the target data item's location in the representational space. The second is query augmentation, which generates additional training queries by interpolating between initial queries and target IDs in the representational space, helping the model generalize to new data types.

Foundation models have transformed language and computer vision, but their adoption in scientific domains like computational fluid dynamics has been slower. What will it take for them to play a more significant role in scientific applications?

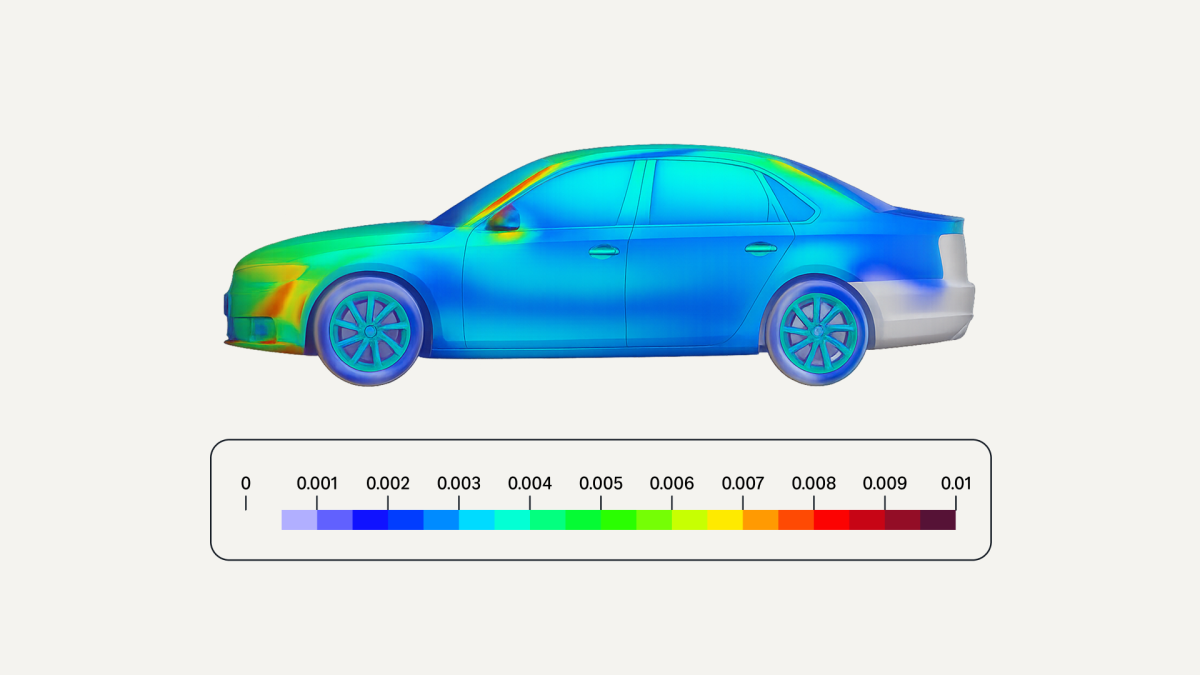

A DrivAerML dataset surface plot of the normalized magnitude of wall shear stress (wall friction coefficient). To help answer this question, Amazon applied scientist Danielle Maddix Robinson explores foundation models’ application to time series forecasting, with both univariate and spatiotemporal data. Scientific foundation models face challenges that large language models don’t: severe data scarcity (since generating high-quality scientific data often requires expensive numerical simulations), the constraints of inviolable physical laws, and the need for robust uncertainty quantification in safety-critical applications.

For univariate time series, Robinson and her colleagues address data scarcity with synthetic pretraining data. The resulting model demonstrated surprising strength on chaotic dynamical systems — not because it was designed for them but because of its ability to "parrot" past history without regressing to the mean, as classical methods do. For spatiotemporal forecasting in domains like weather prediction and aerodynamics, the researchers found important trade-offs between accuracy and memory consumption across different architectures, with some models better suited for short-term forecasts and others for long-term stability.

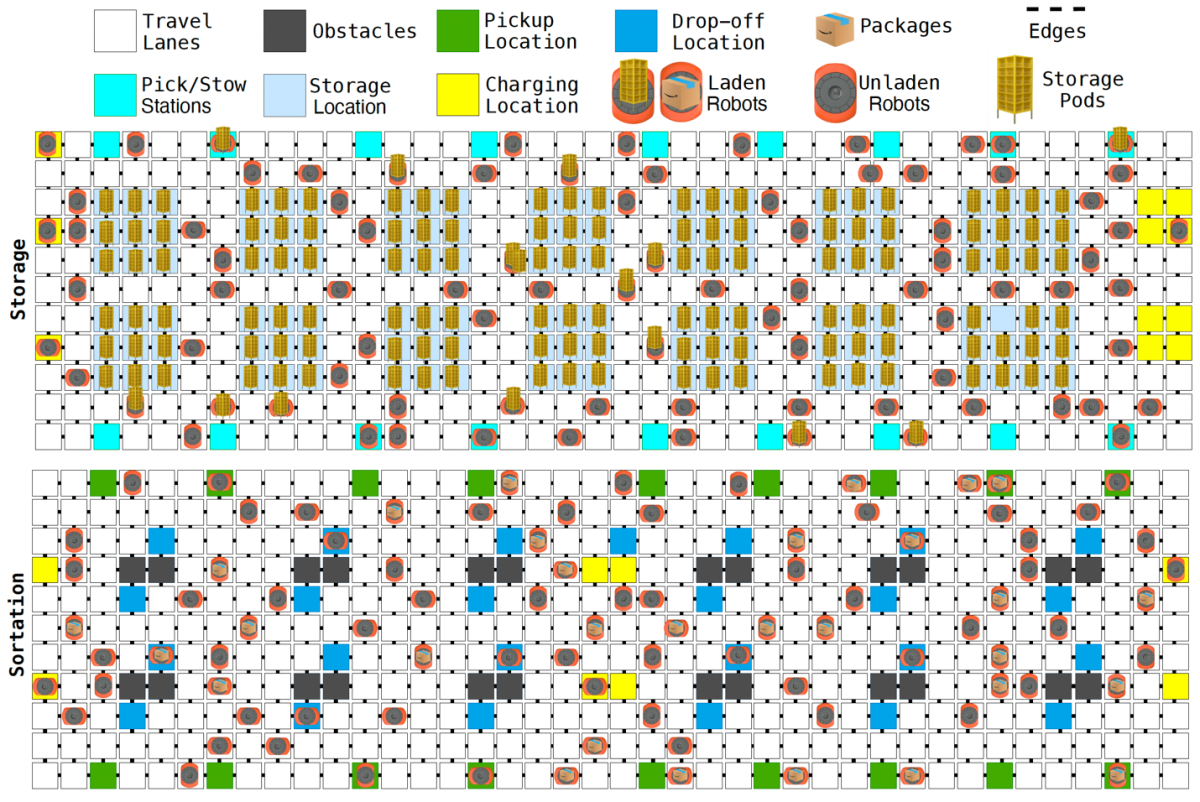

Managing fleets of thousands of mobile robots in Amazon fulfillment centers requires predicting the robots’ future locations, to minimize congestion when assigning tasks and routes. But using the robots’ navigation algorithms to simulate their interactions faster than real time would be prohibitively resource intensive.

Amazon's DeepFleet foundation models learn to predict robot locations from billions of hours of real-world navigation data collected from the million-plus robots deployed across Amazon fulfillment and sortation centers. Like language models that learn general competencies from diverse texts, DeepFleet learns general traffic flow patterns that enable it to quickly infer how situations will likely unfold and help assign tasks and route robots around congestion.

Sample models of a fulfillment center (top) and a sortation center (bottom). Researchers experimented with four distinct model architectures — robot-centric, robot-floor, image-floor, and graph-floor — each offering a different answer to fundamental design questions: Should inputs represent individual robot states or whole-floor states? Should floor layouts be encoded as features, images, or graphs? How should time be handled?

AI agents represent a leap forward in generative AI, a move from chat interfaces to systems that act autonomously on users' behalf — booking travel, making purchases, building software. But how do agentic systems actually work? Amazon vice president and distinguished engineer Marc Brooker demystifies the core components of agents and explains the design choices behind AWS's Bedrock AgentCore framework.

At their heart, agents run models and tools in a loop to achieve goals. The user provides a goal; the agent uses an LLM to plan how to achieve it; and the agent repeatedly calls tools — databases, APIs, services — based on the model's instructions, updating its plan as it receives responses.

But making such systems work in practice requires sophisticated infrastructure. AgentCore uses Firecracker microVMs to provide secure, efficient isolation for each agent session, with startup times measured in milliseconds and overhead as low as a few megabytes. The AgentCore Gateway service manages tool calls using standards like the model context protocol, translating between the LLM's outputs and tool input specifications. When no API exists for a needed action, Amazon's Nova Act enables computer use, letting agents interact with any website by pointing and clicking.

- Research areas

- Research areas

- News & blog

- The latest from Amazon researchers

- The latest from Amazon researchers

- Amazon Research Awards

- Research collaborations

- Overview

- Carnegie Mellon University

- Columbia University

- Hampton University

- Howard University

- IIT Bombay

- Johns Hopkins University

- Max Planck Society

- MIT

- Tennessee State University

- University of California, Los Angeles

- University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

- University of Southern California

- University of Texas at Austin

- Virginia Tech

- University of Washington

- Amazon Research Awards

- Research collaborations

- Overview

- Carnegie Mellon University

- Columbia University

- Hampton University

- Howard University

- IIT Bombay

- Johns Hopkins University

- Max Planck Society

- MIT

- Tennessee State University

- University of California, Los Angeles

- University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

- University of Southern California

- University of Texas at Austin

- Virginia Tech

- University of Washington