“One year of research in neural networks is sufficient to believe in God.” The writing on the wall of John Hopfield’s lab at Caltech made no sense to me in 1992. Three decades later, and after years of building large language models, I see its sense if one replaces sufficiency with necessity: understanding neural networks as we teach them today requires believing in an immanent entity.

Let’s start from the basics: when we teach machine learning, we say that memorization is bad, because it leads to overfitting and prevents generalization. Generalization is good — so good that, to achieve it, we incentivize machines not to memorize, through “regularization”. We even prove theorems — so-called uniform generalization bounds — that guarantee generalization no matter what distribution the data are drawn from, provided we avoid memorization.

But my mother always told me not to generalize, and she had me commit to memory countless useless poems in elementary school. Why am I teaching that generalization is good and memorization is bad, when I was taught the opposite?

Biology vs. technology

Machine learning has historically drawn inspiration from biology. But biological systems have hard ontogenic and phylogenic memory bounds: our synapses cannot memorize everything we experience, and our DNA cannot transmit the knowledge we’ve accumulated to our descendants. (As an educator and father, I often wished I could upload what I have learned into my students and kids. I haven’t figured that one out, but can we at least do it for AI models?) Furthermore, biology imposes a strong evolutionary bias toward minimizing inference latency: when facing an animal in the wild and having to determine who’s whose meal, we can’t reason through all past memories lest the decision be made for us.

In other words, biological systems are forced to adopt inductive learning, using specific data from the past (or a “training set”) to devise a process for handling any future data. Success in inference from inductive learning (or more simply, induction) relies on the so-called inductive hypothesis, that past performance can guarantee future rewards (the primate species called “financial advisor” has evolved out of this belief).

Technology does not have the limitations of biological systems: there are no hard memory bounds (we can always add more storage) and no hard computational bounds (we can fire up more computers), at least until we hit cosmic limits. If we accept that machines do not have the same limitations as biology, what is the best inference paradigm for them? That is, given a training set and a test query, how can they devise the best answer?[1] If we want our model to operate in the constantly evolving real world, we shouldn’t assume the existence of a single distribution from which all data are drawn, in principio, nunc, et semper.

Inference that allows processing the training data at inference time is called transductive inference, or transduction. Transduction calls for us to memorize and reason, unlike induction, which wants us to generalize and forget. To perform optimal inference with respect to any hypothetical distribution in the future, one must memorize past data and, only when presented with a specific query, deploy “reasoning” skills and access memory to compute the best possible answer to that query.

Induction calls for forgetting what does not matter during training, under the assumption that the training set is representative of all future data. But in reality, one cannot know what data will be useful when, so memorization is wise if one can afford it, even when the data — like the writing on John Hopfield’s lab’s wall — does not make sense in that moment.

Transductive inference from inductive learning

Uniform generalization bounds may seem powerful because they are valid for any distribution; but for them to work, there can be only one distribution from which both past and future data are independently sampled. Paraphrasing the statistician Bruno de Finetti, this distribution does not exist in any objective or material sense. It is an abstract concept, the product of our imagination. Something we concoct to guide our intuition and analysis.

The inductive hypothesis is fundamentally not verifiable: any finite training data could have been drawn with identical likelihood from infinitely many distributions, so even if there was a single true one, how would we know which? Once the present is past, we cannot repeat the experiment. The inductive hypothesis is a statement of faith and uniform generalization bounds an expression of hope, not quite within the scientific realm.

Don’t get me wrong: hope can pay off. The future often does resemble the past. But many of the mechanisms that generate the data we care about today, in business, finance, climate, and language, evolve over time. The same word can carry a different meaning today than it did a century, or even a decade, ago. The point is that whether the inductive hypothesis holds or not cannot be known ahead of time.

Solomonoff inference

What if we forgo generalization and embrace memorization and reasoning? Is that what LLMs are doing? If so, where are they heading? What does the limit of optimal transductive inference look like?

The answer was given in 1964 by the mathematician Ray Solomonoff and is now known, somewhat confusingly, as Solomonoff induction. I will refer to it as Solomonoff inference, which can be thought of as the limit of scaling laws when we allow memory, computational capacity, and time to grow to infinity.

Solomonoff inference is optimal with respect to all computable distributions, averaged with respect to the universal prior. The Church-Turing thesis predicates that any physically realizable mechanism belongs to this class. While infeasible in practice, since it requires infinite resources, Solomonoff’s algorithm is quite simple: execute all programs in increasing order of length until one manages to spit out all the data observed up to now, bit by bit, if it terminates.

The optimal algorithm is basically a lookup table with a switch. There is no insight, no knowledge, not even learning. If presented with the same query twice in a row, the optimal algorithm would repeat the same procedure all over, having learned nothing from past experience.

Solomonoff inference is quite unlike neural networks, which are trained by comparing gradient vectors in a high-dimensional space, where the data are embedded. But could it be that, as we scale LLMs to larger and larger sizes, their behavior is beginning to resemble Solomonoff inference? After all, LLMs are known to memorize, albeit imperfectly, and they can perform universal computation, at least if augmented with a scratchpad. Indeed, LLMs are already able to perform rudimentary transductive inference, now known as “in-context learning” — somewhat confusingly, as it involves no learning: if presented with the same context twice, an LLM would repeat the same process, with no improvement from experience.

So, if LLMs were to begin to perform Solomonoff inference, would they become “superintelligent”? Given no accepted definition of intelligence, let alone its superlatives, many tacitly assume inference performance as its proxy: “smarter” models (or students) perform better on tests, whether the SAT, GRE, or BAR, or the famed IMO math competition. The higher the score, the more “intelligent” the model must be! But the absolute best would be Solomonoff’s algorithm, and no matter what one’s definition of intelligence is, Solomonoff’s algorithm cannot meet it: if by mistake the IMO printed each question twice, Solomonoff’s algorithm would redo the same work twice, not exactly what most would call “intelligent” behavior.

As an analogy, an “inductive student” is a diligent pupil who studies the textbook and completes all homework assignments and practice problems before showing up at the exam. So long as the questions are close enough to practice problems, the inductive student does well. On the occasional odd (or out-of-distribution, as a believer in induction would say) question, the inductive student may not do as well.

By contrast, the “transductive student” does not study at all and instead shows up at the exam with the textbook in hand. Only after reading the first question does the transductive student go through the book to find all the pieces needed to assemble an answer. The student could, in principle, repeat the exercise all the way to the last question, learning nothing in the process. As Solomonoff showed us, there is no need to be smart if one has unbounded time, memory, and computational power.

Do we want models that perform well on benchmark exams, or is the kind of “intelligence” we want something else? Fortunately, inductive and transductive inference are not mutually exclusive. In fact, their difference is quite subtle, as one could frame either as a special case of the other, and the two coincide when the data are independently and identically distributed.

What matters is that LLMs are inductively trained transductive-inference engines and can therefore support both forms of inference.[2] They are capable of performing inference by inductive learning, like any trained classifier, akin to Daniel Kahneman’s “system 1” behavior — the fast thinking of his book title Thinking Fast and Slow. But LLMs are also capable of rudimentary forms of transduction, such as in-context-learning and chain of thought, which we may call system 2 — slow-thinking — behavior. The more sophisticated among us have even taught LLMs to do deduction — the ultimate test for their emergent abilities.

AI models’ inferential abilities are improving organically with scale — although they’re still inferior to those of the best humans on most tasks. But they are also being actively fostered through the use of formal-verification tools such as LEAN, as is happening at AWS. One could call this paradigm Solomonic learning: embrace memorization and foster reasoning, yet do not eschew induction. Simple tasks that might benefit from past experience can be solved inductively, saving time and energy, but doing so requires “understanding” and “insight”.

Given that paradigm, the question is what classes of models best support Solomonic learning.

Architectures for Solomonic learning

Solomonic learning requires models that can memorize and perform computation at inference time, in addition to performing ordinary induction. The model architectures therefore need eidetic (verbatim) working memory, which could fade over time, to support computation; but they also need long-term memory to easily retrieve facts from the distant past (the purpose for which humans invented the printing press).

To adapt to changing conditions, they need their long-term memory to decay in synchrony with changes to the mechanisms that generate the data they process. Evolution does that for biological agents, to the benefit of the species rather than any one individual. Transformers, the workhorses of current LLMs, have eidetic (verbatim) memory “in context”, but only until tokens slide out of context. They also have permanent memory “in weights”, but training data are not accessible eidetically from the weights, and there is no long-term adaptation. Eidetic long-term memory can be accessed through RAG (retrieval-augmented generation), but in current Transformers, RAG is not integrated into the primary (autoregressive) inference loop.

Stochastic realization theory and input-dependent state space models

Half a century ago, stochastic realization theory tackled the question of how to model sequential data for downstream decision or control tasks. The “state” of the model was defined as the function of past data that is sufficient for the future, meaning that, given the state, one can discard all past data and predict future data as well as if the data had been retained.

The trivial state is the data itself. An optimal state, by definition, supports an optimal predictor, which is one that makes the prediction error unpredictable. Then, by construction, the state contains all the “information” in past data. During training, the states of LLMs are their weights, so it should be no surprise that next-token prediction is the method of choice for training them. During inference, the state of a Transformer-based LLM is the sliding window of tokens, which is “deadbeat”, meaning that it decays to zero in finite steps without a driving input.

In general, as we observe more and more data during both training and inference, the state must grow apace. In the 1970s, an unbounded state was unthinkable, so the key question was how to find a fixed-dimensional state that is optimal even as the data volume grows to infinity. Therefore, stochastic realization theory focused on Markov processes that admit a finite-dimensional state.

Since any finite-memory sequence could be modeled as the output of a linear model driven by white zero-mean Gaussian noise, the attention was all on linear state-space models (SSMs). While simplistic, such SSMs were good enough to take us to the moon. Today, an unbounded state is not unthinkable. Nonetheless, LLM weights are fixed after training, and the context size is imposed by hardware limitations. So we need richer architecture families.

As an aside, I wish to stress the distinction between the model, which is any state-space realization that supports optimal prediction (there are generally infinitely many), and the system, which is the “real” mechanism that generates the data. The system is unknown and unknowable; the model is tangible and entirely under our control. Although as engineers we are trained to believe that models of the world converge to the “true” system as they improve, this position — known in epistemology as "naïve realism" — is scientifically indefensible.[3]

To stress the dichotomy between the system and the model, in 1979, Anders Lindqvist and Giorgio Picci derived an equation that, four decades later, is at the heart of diffusion models. In a dissipative physical system, time cannot be reversed, bu it can in a model of that system, for instance a Gaussian SSM. The structure of the reverse diffusion in the model is the same as the forward diffusion, a fact that is exploited in diffusion models for image generation.[4]

Unlike deadbeat Transformers, SSMs have unbounded memory, but it fades, making them incompatible with optimal transductive inference. Again in the 1970s, the late Roger Brockett triggered a burst of interest in input-dependent state-space models, where some of the parameters are affected by the input, the simplest case being when they interact (bi-)linearly with the state. Art Krener showed that such bilinear SSMs can approximate an arbitrarily complex nonlinear (smooth) model. Alberto Isidori and coworkers extended stochastic realization theory to bilinear models, but still with an eye to making the state as small as possible.

Even 30 years later, prior to the deep-learning revolution, when we used input-dependent SSMs to generate videos of dynamic textures, we were still focused on keeping the state dimension as small as possible, encouraged by the fact that 20 states were sufficient to animate and control the rendering of waterfalls, flames, smoke, foliage, talking faces, and other stationary processes. Thanks to the reversibility of the model, we could even make smoke or steam move faster, slower, or backwards!

Deep learning twisted Occam’s razor by trying to make the embedding dimension of the training state (the weights) as large as possible, not as small as possible. Dimension is only an upper bound on “information,” and the key to induction is to limit the “information” in, not the dimension of, the trained weights.[5] Two decades later, we stacked SSMs into a neural architecture by feeding the (input-dependent) prediction residual of one layer to the next.

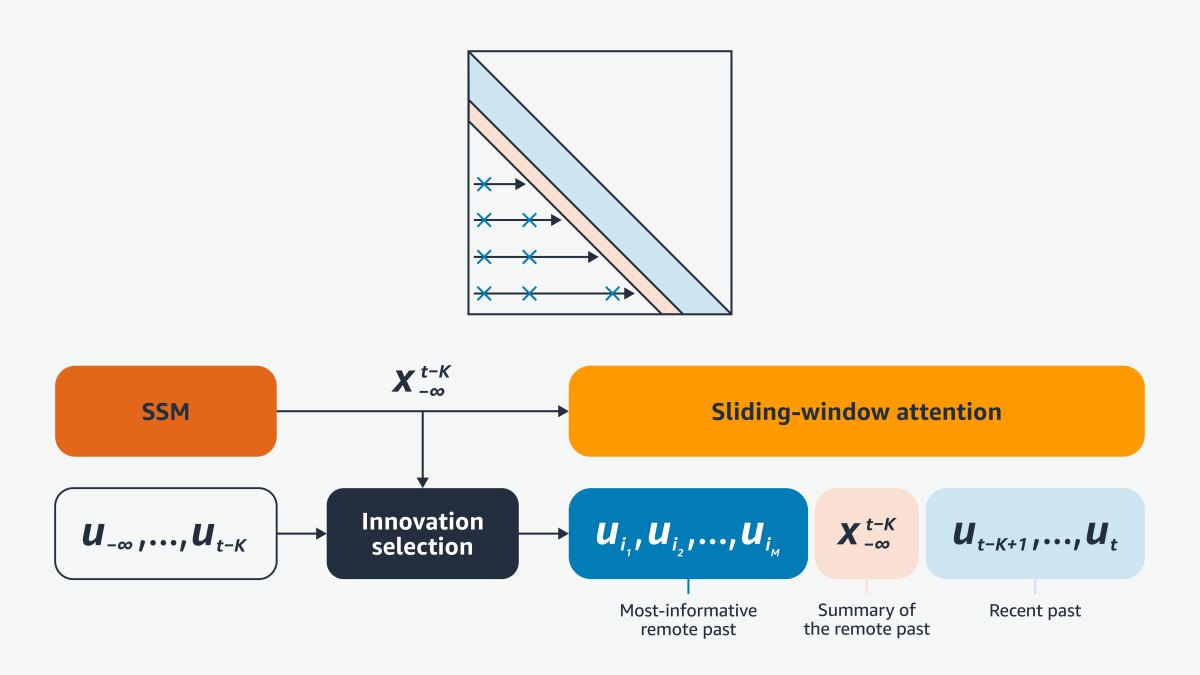

A breakthrough came with Mamba, which showed that efficient implementation at the hardware level is key. When Mamba is stripped down (as it is in appendix E of our recent paper on architectures to support transductive inference), it is a stack of bilinear SSMs (which Mamba’s developers call “selective state-space models”) restricted to non-interacting states (diagonal dynamics), so it can be implemented efficiently in hardware.

Diagonal SSMs are disjoint from and complementary to Transformers. Autoregressive (AR) Transformers have nilpotent dynamics, meaning that the state transition matrix becomes zero in a finite number of steps in the absence of external input. Mamba has diagonal dynamics, and nilpotent matrices cannot be diagonalized. Diagonal SSMs support infinite fading memory; AR Transformers support finite eidetic memory, and neither is general. Instead, any general (bi-)linear system can be converted to a so-called canonical form, also derived in the 1970s, which can support both eidetic and fading memory.

Meet B’MOJO

B’MOJO is a family of architectures based on canonical realizations that include Transformers, Mamba-like SSMs, and any hybrid combination of the two. There are combinatorially many options, and the name of the game is to find those that are sufficiently general to support different memory regimes yet can be efficiently mapped to specific hardware in order to scale. We plan to release basic versions of B’MOJO both for GPU hardware and for Amazon’s Trainium hardware, so they can be easily compared with existing Transformers, SSMs, and hybrid architectures.

The writing on the wall

While a representation of the “true” system is fundamentally elusive, lending credence to the writing on the wall of John Hopfield’s lab back in 1992, building model realizations is a concrete exercise grounded in data. LLMs, where the “L” refers not to natural language but to the inner language that emerges in the trained model at scale, are stochastic realizations trained inductively as optimal predictors and coopted for (suboptimal) transductive inference and generation. If the training data subtend latent logical structures, as do sensory data such as visual or acoustic data, models trained as optimal predictors are forced to capture their statistical structure.

Thus, LLMs in our parlance include so-called world models trained with visual, acoustic, olfactory, tactile, and other sensory data. The model is indifferent to whether tokenized data express some abstract concept in natural language or a physical measurement process in finite precision. The resulting LLMs can represent concepts and meanings, including physical concepts such as the laws of physics, and can in principle reason, although at present they appear to be mostly building ever bigger lookup tables. Regardless, as stochastic dynamical models, LLMs can be controlled, probed with causal interventions, made observable, and studied with the tools of dynamical-systems theory.

A model is an abstraction of the underlying world — not a representation of it, because there is no objective “it” to re-present, but a realization of it, made real through the only objective entity, which is the data. Synthetic data are just as real to the model as data produced by a physical measurement process, and aligning the two is the essence of perception, for this reason often referred to as controlled hallucination.

While much of the popular discourse denigrates hallucinations[6] as something to be avoided, the ability to hallucinate is necessary for reasoning. The question is not how to avoid hallucinations but how to control them, which is the process of alignment. Architectures designed for decision and control can help, and decades of work in dynamical systems and controls may provide insights — hopefully without the need to resort to divinity, as the writing on the wall suggested.

Footnotes

[1] Note that "best" does not mean "correct." If the data is insufficient to identify the correct conclusion, even the best answer can be wrong.

[2] The simplest form of inductive learning for transductive inference is transductive fine-tuning, a form of meta-learning: past data is used to "meta-train" a model that, at inference time, is fine-tuned with a small number of examples ("few shots") to perform a new task. LLMs take this program steps further, by using sequential data with a latent logical structure (not only natural language but also video, audio, and other signals) to produce an “inner language” (we call it "Neuralese") that can then be co-opted for transductive inference.

[3] Quoting Bertrand Russell: “We all start from 'naïve realism,' i.e., the doctrine that things are what they seem. ... The observer, when he seems to himself to be observing a stone, is really, if physics is to be believed, observing the effects of the stone upon himself. Thus science seems to be at war with itself: when it most means to be objective, it finds itself plunged into subjectivity against its will. Naïve realism leads to physics, and physics, if true, shows that naïve realism is false. Therefore naïve realism, if true, is false; therefore it is false.” Even the International Vocabulary of Metrology has dispensed with the notion of “true value” in its most recent revisions.

[4] In the paper that introduced diffusion models for image generation, the reverse-diffusion equation was attributed to a 1949 work of Feller. However, forward diffusion in the form in use today was not derived until 1960, so neither was reverse diffusion. Later references attribute the reverse-diffusion equation to a 1982 paper by B. D. O. Anderson, which, however, did not introduce it but instead described it, based on the 1979 paper of Lindqvist and Picci, correctly referenced in Anderson’s work, and extended it to more general models different from those in use in diffusion models today. The correct reference for the reverse-diffusion equation used in diffusion models is therefore Lindqvist-Picci 1979.

[5] I use quotes because defining information for the weights of a trained model entails some subtleties, but it can be done.

[6] "Hallucinations" are data generated by a model that are statistically compatible with the training set (in the sense of high likelihood under the trained model), yet "wrong", i.e., individually inconsistent with constraints that some external oracle has deemed "true" ("facts", or "axioms"). In other words, hallucinations are the product of any generative model. Outside formalized domains such as math or code, there is no objective "truth", so the oracle is replaced by an accepted knowledge base, which depends on the application. For "common sense" knowledge, the base is generally a large corpus of (more or less) verified facts, such as WikiData. Outside formalized domains, including the law, there is no guarantee that the facts or "axioms" are mutually compatible.