Every day, Amazon ships millions of parcels. Single orders often include multiple products, and while Amazon employs hundreds of thousands of people at its fulfillment centers worldwide, those employees sometimes need an assist to handle the volume. They get it from a fleet of mobile robots.

A typical Amazon fulfillment center contains fleets of robotic drives, autonomous mobile robots that transport goods. While each has a heroic name — Hercules, Pegasus, and Xanthus — the fact is that these drives perform the mundane but necessary tasks required to efficiently deliver goods to customers’ doors.

Hercules, as its name attests, combines strength and speed. It brings goods from inventory to employees for packing. Pegasus, whose name evokes the winged horse of Greek mythology, sorts parcels by zip code or delivery route. Xanthus, named for the immortal horse that drew Achilles’ chariot, also sorts but can do other tasks as well.

Robotic drives complete their tasks while safely navigating a constantly changing world that includes employees, other mobile robots, obstructions, and even congestion. They must not only deliver the right product to the right place, but do it at the right time.

Air traffic control

That is why Amazon has embraced shared autonomy, which allows drives to make some decisions independently while still taking overall direction from centralized planning software.

Tye Brady, Amazon Robotics’ chief technologist, likens it to an air traffic control system: The flight controller provides the route and departure/arrival times, but the pilot takes off, flies, and lands the jet using their best judgment.

The process begins when an order arrives. Algorithms gauge both product availability and the ability to meet delivery windows. When the right match is found, that information is sent to a specific fulfillment center, where centralized planning software begins to orchestrate the safe, efficient movement of those robot drives to help meet the delivery date.

“Once the centralized planner creates this schedule, it assigns tasks and routes to the drives,” Brady explained. “The drives have enough smarts to move safely around humans, communicate with nearby robots so they do not collide, and report any problems like spills or obstructions back to the controller. If a drive sees that a path is blocked, for example, the planner says, ‘That’s OK. Let me see if I can find you a new route.’”

Fenway Park parking puzzle

After an order comes in, the first in motion is Hercules, which fetches goods from inventory so employees can pack and label them for shipping. If an order involves more than one item, the centralized planner schedules several drives, each carrying one or more products, to arrive one after the other, so the associate can more easily assemble the order.

Hercules is the embodiment of Amazon’s goods-to-employee approach to fulfillment. Instead of asking employees to search for goods on the shelves, Amazon uses robots to bring products to employees at fixed packaging stations.

There are several reasons Amazon favors a goods-to-associate flow, Brady noted. First, asking employees to rummage through bins to find the right product is repetitive and inefficient. A robot can do this task, allowing employees to focus on more complex tasks.

The benefit of this approach is multiplied when a facility is optimized for robots. For example, Amazon stores goods on four-sided shelves called pods, which contain randomly sized bins of products. Hercules slides under the pod, which weighs up to 1,000 pounds, lifts it off the ground, and delivers the entire pod to the packing station.

Because only robots access the pods, Amazon can cluster pods closer to one another, which increases the volume of goods it can store in its warehouses. If a pod’s product is popular, drives will shuttle it closer to the packing stations. If demand cools, they will shift them to the back.

However, clustering sometimes creates what Brady, who works in Boston, calls a Fenway Park parking puzzle.

“That’s when your car is boxed in by 10 other cars and you want to get it out efficiently,” he said. “The same thing happens with clustered pods, and our algorithms solve it all the time using a team of robots. Better yet, they will not charge you $80 to park there as well!”

Hercules

Hercules itself is a fourth-generation drive designed to navigate structured fields, floors that contain a grid of encoded markers. By reading the markers with its downward facing camera, it can find its position and the location of any pod.

Hercules mounts a forward-facing 3D camera that identifies people, pods, other robots, and obstructions. The robot uses these images to make safe decisions quickly if an issue arises. The drive is also programmed to respond safely if the electricity goes out or the Wi-Fi crashes.

Hercules also communicates with other robots and humans with wearable Wi-Fi transmitters called Tech Vests. This enables it to identify the location of humans and robots beyond the range of its sensors, so it can plan a route that steers clear of them.

Hercules drives operate in parallel — even when some need to pause their operations. “If ten or even one hundred drives need to recharge their batteries or stop to run diagnostics, that’s OK,” Brady said. “There’s just so many of them that the rest of the swarm can replan and reroute. There’s no single point of failure.”

In 2018, Amazon unveiled Pegasus, a drive used to take finished parcels from employees and sort them by zip code or delivery route within the fulfillment center.

The robot is built on a Hercules drive and uses a structured field to navigate the sortation center. Like Hercules, the drive is fully sensored and operates safely around people, other robots, and obstructions. The big difference between the two robots is that Pegasus mounts a mini-conveyor belt on top of the puck-like drive.

Sorting, however, is different than moving pods.

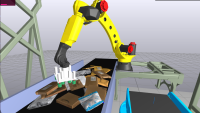

It starts when a truck delivers a load of packed and labelled parcels. These go onto a conveyor belt that goes upstairs to the facility’s mezzanine. There, employees (or robotic arms) scan each parcel’s address and then place it onto the Pegasus mini-conveyor. The planner assigns the robot a route based on the address. Pegasus then navigates around an array of holes in the floor. When it gets to the right one, the conveyor drops the package down a chute that takes it to the correct loading dock below.

X-bot

Physically, Xanthus, also called X-bot, looks like a lightweight version of Pegasus, which makes sense, as Amazon doesn’t need a drive designed to lift 1,000-pound pods for delivering twenty-pound parcels.

This makes the drive less expensive to build and deploy in large numbers. Xanthus also has upgraded sensors that enable it to detect people, robots, and obstructions from farther away than any of Amazon’s other mobile robots.

What really sets the new drive apart, however, is its flexibility.

“It’s a clever robot, and its sensor package is well-suited to moving in busy environments,” Brady said. “We did that intentionally to make it more of a jack of all trades. We started it on sortation, but in the future, we see a lot more potential applications for it.”

Some of those uses and design features were crowd-sourced from Amazon employees.

“We issued a challenge to our employees about three years ago,” Brady said. “We asked them, ‘What would a very low-cost mobile robot look like?’ About a third of our employees responded, and we grouped some of them into teams to move those ideas forward. We used several of those ideas in the final design.”

It's a clever robot, and its sensor package is well-suited to moving in busy environments. We did that intentionally to make it more of a jack of all trades. We started it on sortation, but in the future, we see a lot more potential applications for it.

Xanthus’ flexibility could make it a game changer in Amazon’s fulfillment centers. Yet Brady thinks of it as evolutionary, not revolutionary. Xanthus is the next step for Pegasus, just as Hercules is the fourth iteration of Amazon’s original pod drive. In both cases, the new drives are smaller, faster, smarter, and safer than the ones they replaced.

“The job of our engineers is to take these complicated tasks and ideas and simplify, simplify, and simplify until they become reality,” he said. “The best things that we do are really very simple. And because we have gained this world-class capability in autonomous mobility, we can unlock the lessons we’ve already learned inside our fulfillment centers and develop new robots that are extensions of what we already do.

“This work exemplifies one of the company’s newest leadership principles of striving to be the Earth’s best employer,” Brady adds. “That principle suggests that leaders work every day to create a safer, more productive, higher performing, more diverse, and more just work environment. That’s the role of our robots, to augment the work of our employees, making our fulfillment centers safer and more productive.”