This is a condensed version of a talk that Amazon vice president and chief technology officer Dr. Werner Vogels gave at the AI for Good Global Summit in July 2025 in Geneva.

In January 2007, my mentor, friend, and fellow computer scientist Jim Gray, a Turing Award laureate often described as the father of modern database systems, disappeared while sailing solo to the Farallon Islands off San Francisco. Despite deploying every technological resource imaginable, from repositioning government satellites to mobilizing thousands of recruits through Amazon's Mechanical Turk to analyze satellite images, we never found him. If we had today's AI resources, would the result have been different? Maybe. There are things that we can do now that we definitely could not do in 2007.

While Jim’s friends were able to use their private-sector relationships and government clearances to access real-time satellite data, most vulnerable communities remain invisible in our digital representations of Earth. The Haiti earthquake of 2010 made this painfully clear. International rescue teams arrived in Port-au-Prince to find a city that was, for all practical purposes, unmapped. Emergency responders had GPS coordinates but couldn't navigate because the maps they had couldn't distinguish between alleys and major roadways or locate critical infrastructure like hospitals and shelters.

The data divide

The situation in Haiti isn't unique. Consider Makoko, a community in Lagos, Nigeria, that is home to more than 300,000 people living on stilt houses in the Lagos Lagoon. On most maps, this entire community appears as a blank blue spot. These people are effectively invisible, unable to access basic services because they don't exist in our spatial data models.

The reason for this omission is simple: most maps are created for commercial purposes, not humanitarian needs. We meticulously map shopping districts in major cities but leave vast swaths of the developing world uncharted. This creates what I call the "data divide", a disparity in data access that mirrors and exacerbates existing social inequalities. When we only map what's profitable, we perpetuate these inequalities and leave the most vulnerable communities exposed.

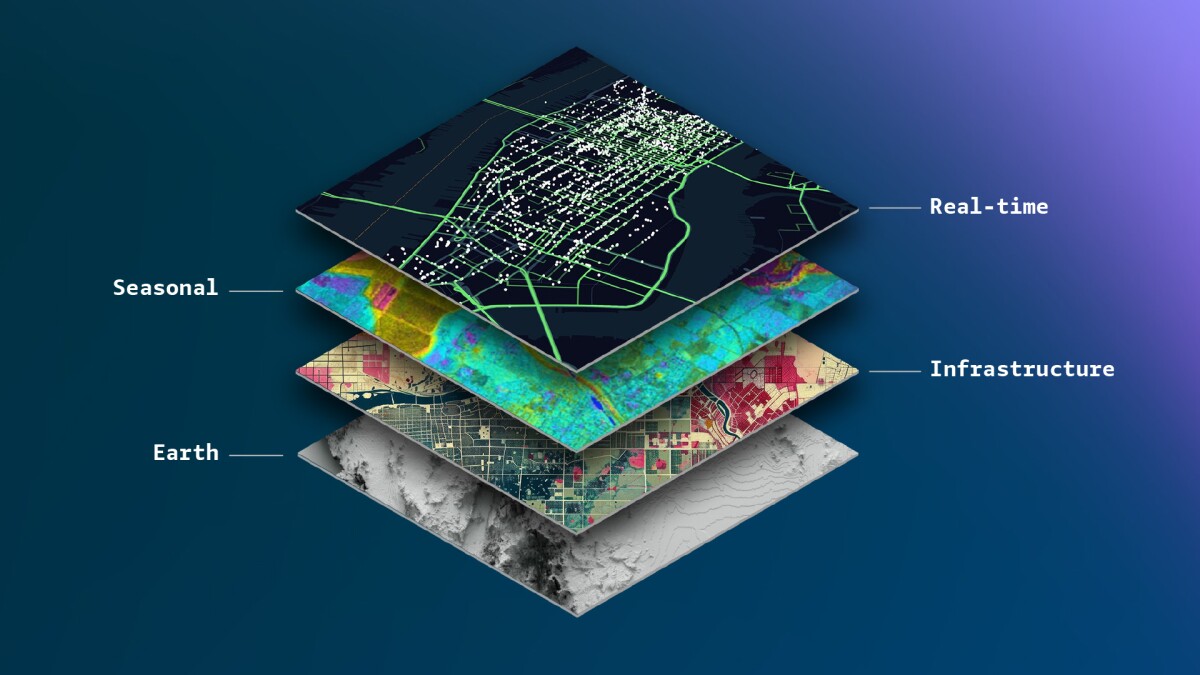

Now, if you think about maps, there's not just one map of the earth. The moment you have a traditional map in your hand, it is out of date. Effective maps are multilayered systems operating across different timescales.

First, there's the Earth layer, the slow-changing geographical features that remain constant over decades or centuries. The Himalayas or Amazon Basin won't be moving anytime soon. Then there's the infrastructure layer — roads, bridges, and buildings that evolve over years. Next comes the seasonal layer, which tracks changes in vegetation, water levels, and other environmental factors that shift with the seasons. Finally, there's the real-time layer, a constantly fluctuating stream of data about human activity, weather patterns, and emergency situations.

Humanitarian mapping must integrate all these layers. During a flood, for example, we need real-time data about water levels (real-time layer), historical flood patterns (seasonal layer), existing drainage infrastructure (infrastructure layer), and underlying topography (Earth layer). Combining these data streams requires sophisticated AI models that can handle multiple data types and temporal scales.

Democratizing Earth data

The good news is that the tools for data collection have become much more accessible. The number of Earth observation satellites has exploded from about 150 in 2008 to over 10,000 today. These satellites offer not just high-resolution imagery but advanced sensors like multispectral imagers, radar, and lidar.

In the aftermath of the Haiti earthquake, roughly 600 members of the OpenStreetMap community were able to create the first reliable crisis map within 48 hours. It only took two days to go from unmapped to mapped. This crowdsourced map became the default navigation tool for every major responding organization, from the UN to the US Marine Corps. OpenStreetMap has since evolved into a global platform for collaborative mapping, with spinoffs like the Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team (HOT) and Missing Maps focusing specifically on crisis response.

Drones have emerged as a powerful complement to satellites, filling gaps where satellite imagery is insufficient or too expensive. The Mapping Makoko project trained local residents to pilot drones and map their community. This initiative did more than create a map; it empowered residents with a tool for political advocacy, demonstrating the power of democratized data collection.

While satellites and drones provide macro-level data, mobile devices and Internet-of-things (IoT) sensors offer granular, real-time information. With over eight billion mobile devices globally, we have an unprecedented opportunity for crowdsourced data collection. In Southeast Asia, the Grab app (a super-app providing everything from ride hailing to food delivery) has created detailed maps of previously unmapped areas simply by tracking the routes of its drivers, who are familiar with neighborhoods, alleys, and unmarked homes. Similarly, India's Namma Yatri app connects auto-rickshaw drivers with passengers while simultaneously generating accurate street maps of informal settlements.

IoT sensors embedded in infrastructure provide another layer of real-time data. Environmental sensors tracking air quality, water levels, or seismic activity can feed directly into mapping systems, creating a dynamic representation of a community's current state.

Building with open data

During a recent visit to Rwanda, I saw firsthand how data-driven mapping can transform healthcare delivery. The Rwanda Health Intelligence Center uses real-time data to track healthcare utilization across the country. By combining this with geospatial data, they've calculated the maximum walking distance for pregnant women to reach a health center. This data directly informs where to build new facilities, optimizing resource allocation.

Another inspiring example is the Ocean Cleanup project, which aims to remove 90% of ocean plastic by 2040. They've developed a river model using drones, AI analysis, and GPS-tagged dummy plastics to predict plastic-flow patterns. This data-driven approach allows them to position their cleanup systems in the most effective locations, while AI-powered cameras on bridges identify different types of plastic in real time.

The sheer volume of geospatial data — hundreds of petabytes from satellites, drones, and IoT sensors — requires robust infrastructure. Cloud platforms like Amazon S3, which processes over a quadrillion requests every year, make it possible to store and process this data at scale. Our Open Data Sponsorship Program further removes barriers by covering costs for high-value public datasets, including OpenStreetMap, Sentinel-2 imagery, and various environmental-sensor data.

Planetary problem-solving machine

The combination of open data, advanced AI models, and cloud infrastructure creates what I call a planetary problem-solving machine. This trio can tackle challenges that were previously intractable. Open data ensures transparency and verifiability, while AI extracts insights that would be impossible for humans to discern.

When we have data that could save lives or protect the environment, keeping it private is morally indefensible. The United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals all depend on geospatial data. Whether it's ending poverty, achieving food security, or combating climate change, every goal requires location-based data to measure progress and guide interventions.

The question for all of us is, what data do we have that could be useful to others? And more importantly, what data can we open up? If we don't act, we risk perpetuating a world where the most vulnerable remain invisible, where disasters are compounded by lack of information, and where progress is measured only in places that are profitable.

It is for this exact reason, that in 2024 I launched the Now Go Build CTO Fellowship. Bringing together technology leaders from non-profits and social good organizations that are working to address climate change, disaster management, healthcare accessibility, food security, education and pairing them with experts at Amazon, AWS and beyond. I’ve seen first-hand, how these Fellows are using data to solve the world’s hardest problems, whether that’s measuring crop yields, connecting surplus food with charities and families, or piloting drones in conflict areas, none of which is possible without maps.

Maps have always been more than navigation tools: they're instruments of power. In the digital age, they're becoming tools of justice, healthcare, and environmental protection. By making the invisible visible, we can create a more equitable world.

Now go build.